Throughout human history, throughout the world, the majority of babies have been born at home. In the last few decades however, in many countries, hospital birth has been promoted as being “best”. So is hospital birth best? This is a question I discuss frequently in the UK, and it has been an increasing concern for me in Malawi.

Since 2012 homebirth in Malawi has been technically illegal. This was in response to the very high maternal and infant death rate. The majority of these deaths are attributed to infection or haemorrhage. Many births were being attended by traditional birth attendants rather than formally qualified healthcare workers https://www.kfw.de/stories/society/health/malawi-minimising-birth-related-risks/. Official documents and commentaries generally follow the narrative that by giving birth in a health facility women would experience some form of protection from infection and haemorrhage.

Two of my three children were born at home. I support safe and happy homebirths regularly https://yourmidwife.org.uk/faq/. I was therefore immediately interested by the Malawian requirement for women to attend a healthcare facility to give birth. The reality of my experience here raises major questions. Although the issues are different in the UK and in Malawi, I feel that there is often very little challenge to the prevailing view in both places which assumes that women will leave their home for birth. In response to the question “is hospital birth best?”, perhaps we need to start with questioning how we define best. I am very clear with my clients that my overwhelming priority is safety of mother and baby, but we need to balance risks and benefits. However, safety is not only a physical concept. Many people feel safest at home, and feel under threat or hyper-vigilant in a hospital setting. Adrenaline, the “flight or fight” hormone, opposes the action of oxytocin- the hormone fundamental to safe and effective labour and birth.

In Malawi, women are leaving their homes to attend often very crowded facilities, where they are in extremely close contact with other people. Each household and community has a unique biome – our immune system, developed to protect us from the bugs we commonly meet. When you go somewhere new, you meet different bugs for which your defences may not be very effective. In UK hospitals we address that potential risk through environmental cleaning, bed spacing, well established personal hygiene practices (including hand washing) and use of sterile gloves and instruments. In Malawi, as I have outlined in previous posts, handwashing by staff in hospitals is uncommon- due to a combination of no soap, intermittent water supply and that it is therefore not an ingrained habit as it is in UK healthcare. I have seen no sterile gloves other than those I brought with me. The hospital does not have a sterilising autoclave and so instruments are simply washed and reused. These things surely increase the infection risks rather than decreasing it? The only factor I can identify which could positively affect infection rates in healthcare facilities is the (intermittent) availability of antibiotics.

I have frequently thought of the way in which historically infections were reported to have been spread by doctors in hospitals. In Vienna in the 19th century Semmelweis recognised that in rate of puerperal infections was massively greater in those whose babies were born in hospital compared to those who remained at home. He came to recognise that it was the doctors who were spreading infection between patients https://www.nytimes.com/2003/10/07/health/the-doctor-who-made-his-students-wash-up.html. Two centuries later I have found myself considering the same issues in Malawi, as I question is hospital birth best? Whilst the reported rates of puerperal sepsis (life threatening post birth infection) are low, it must be remembered that women generally return home within 24 hours – before most such infections will be evident. A woman who becomes suddenly and seriously ill with puerperal sepsis is not going to walk for hours back to the health facility to report it. She will probably die at home, untreated and unreported. So is hospital birth best?

Studies have demonstrated that vaginal examinations in labour are related to an an increased risk of infection. The research was done in hospitals where hand washing and good hygiene practices were the norm. How much greater risk must there be in Malawi? The accepted practice here is that vaginal examinations are expected (and frequent). “Routine” vaginal examinations are common in most UK hospitals, and it is well worth thinking about whether these are actually necessary or appropriate. My practice is only to suggest such an examination if the findings might inform our decision making. Most commonly, if a client is birthing at home I find that internal examination is not necessary, since I can observe the progress of labour in many other ways. I’ll add this to my list of things to write more about here in the future.

I am unclear to what extent the risk of haemorrhage is reduced by bringing Malawian women to health care facilities. Many factors increase the chance of haemorrhage, but many (such as malnutrition) are not addressed by place of birth. Exhaustion and stress are known to have adverse impact on the normal hormone cascade after birth which leads to the safe separation of the placenta and associated strong and sustained contraction of the uterus. Whilst it is argued that hospital care is needed for management of bleeding, I question (as in the UK) what proportion of significant bleeds happen because the woman is in hospital in the first place. This is another issue I’ll pick up & write more about UK based practice in a few weeks time. In the rural hospital in Malawi, there are no more ways to manage significant bleeding than I would be able to use at home in the UK. Blood transfusion is not available unless a women is transferred to the regional hospital.

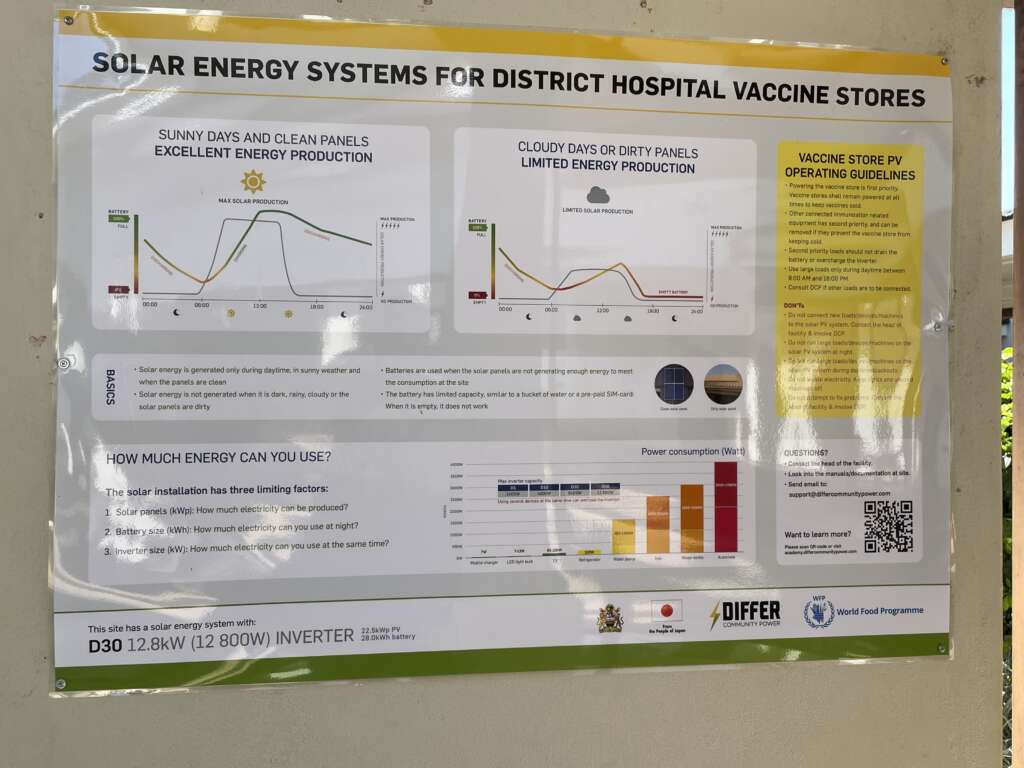

The majority of bleeding after birth is due to poor sustained contraction of the uterus. The drug which is commonly used, both in the UK and in Malawi, loses effectiveness unless it is refrigerated. Because of the frequent interruption to the electricity supply to the hospital there has to be some doubt about how much the drug is working much of the time. It hoped that UNICEF will soon be installing a major solar energy system at Chintheche, as they have at the regional hospital, to ensure continuous electrical supply. The need for refrigeration means that community use of this drug would be problematic in Malawi. Domestic fridges are not a part of rural Malawian homes. At home in the UK I keep my drugs in the fridge and transport them in a cool bag with ice packs when going to a client’s home.

There is an alternative drug which is used as an addition tool in the UK when dealing with major bleeding and after birth. It is stable at the ambient temperatures in Africa. It is a tablet, which can be given orally, or inserted into the vagina or rectum. I have discussed this with many healthcare professionals here, wondering why I have not seen it in use for postpartum haemorrhage. Because it is stable at high ambient temperatures, has a long shelf life and does not require any skill to give it, it seemed to me that it would be sensible for this to be made available in the community ( and in rural healthcare facilities). Women living in remote villages, particularly in the rainy season often simply cannot reach a healthcare facility. If you cannot physically reach a healthcare facility, the question of is hospital birth best becomes irrelevant.

The block to this drug being used is that it can also be used to induce labour, and thus could be used to terminate a pregnancy. In Malawi, termination is illegal. Because this drug could be used for this purpose, women are being denied a life saving intervention. However, I was told that it is sometimes available in the regional hospital, where it is used in the management of incomplete abortion (spontaneous or induced) https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/19/19/12045. It is also sometimes used to induce post term pregnancy. Supply is erratic however, and so many women continue to be deprived of a low risk treatment and are instead exposed to additional risks (or death). I have been curious to discover that this same drug is being issued in general clinics in Malawi as a treatment for gastric ulcers. It would be fascinating to track what happens to this medication in the community https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/meds/a689009.html#:~:text=Misoprostol%20is%20used%20to%20prevent,and%20decreases%20stomach%20acid%20secretion.

So, is hospital birth best? Are the answers the same in Malawi and in the UK? As with so many things, I don’t feel that there is a single clear answer to this question. However, if you prefer an intervention free birth it is important to remember that leaving home to have your baby is an intervention! There are so many variables, to do with the individual woman & her baby, the practices of the care provider (formally qualified or not), the healthcare system and the available resources. The majority of births throughout history have occurred at home. Whilst I accept that interventions can be life changing and life saving for some, I have great difficulty understanding widespread acceptance of hospital being the best place for everyone to give birth. I am glad to be able to return to the UK where I can offer clients balanced and personalised information so that they can answer whether, in their particular situation, is hospital birth best or should they plan to stay at home.