The population in Malawi has grown at an astonishing rate in the last 10 years. There is a very important message that needs to be shared here – of family spacing and the use of contraception. The speed that the population is increasing is very problematic for such a poor country, not simply in terms of cash and service provision, but also in terms of natural resources and food. Everywhere I go there are huge numbers of children and young people. The population of Malawi is estimated to have doubled since 1990 https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/malawi-population/.

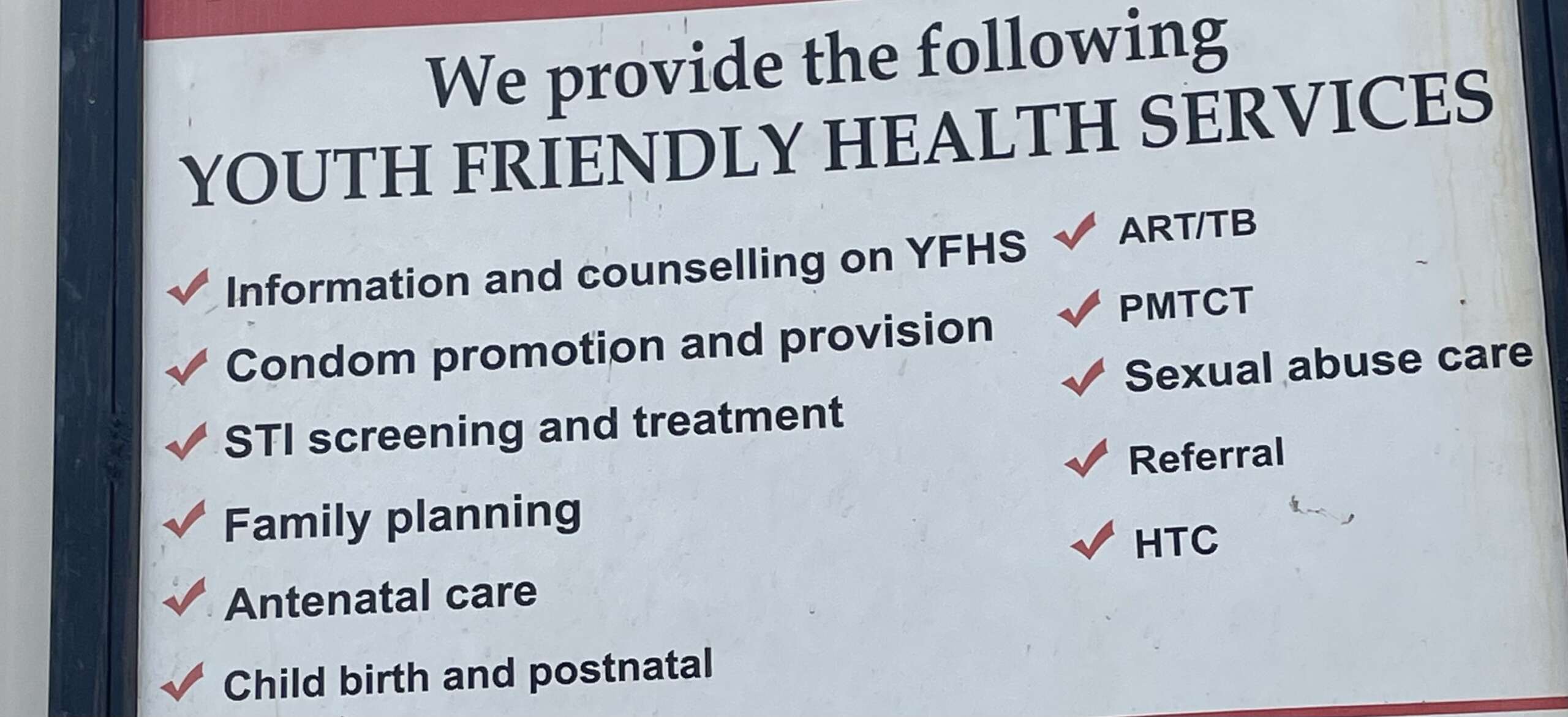

In Malawi, most women will have at least their first child in their teenage years. I have met several 17 year olds having their second or even third babies. Without good family spacing one can only imagine how many babies they could have and how their health might be affected. There are so many factors involved obviously, but one of the biggest differences between Malawi and the UK is the availability of education and appropriate information. Many health centres have big notices (in English) outside stating that they are “youth friendly” but I am far from convinced that the target population can either read or understand the intended message. The majority of the people here never progress beyond primary education and levels of literacy are poor. English may be the “official language” of Malawi, but for the average young person in the villages the only (spoken) English they know is at the level of “good morning, how are you” or the very much overused “give me money”. My suspicion is that the health centre notices have been commissioned by well meaning aid agencies who have not actually lived or directly worked in these communities. This matters, because a teenager who becomes pregnant is automatically excluded from continuing her education. There is also the physical reality that these very young women will have disproportionately poor birth experiences. Last week I was caring for a 15 year old who had an emergency c section (delayed by the need for transport), whose baby is massively brain damaged. Despite my best efforts I could not persuade her guardian that contraception would be sensible for her in the coming years, even though the girl herself agreed. The staff were not willing to focus on the girl’s own wishes. In the UK we advise anyone who has had a c section to avoid becoming pregnant for 6-12 months, in order to allow the uterus to heal properly. The risk of the scar separating in a future labour is something we always have to consider. For a well nourished, healthy woman who has allowed a good interval between pregnancies, the risk is small, though important to consider. For a poorly nourished, underdeveloped body, with minimal family spacing, the result could be catastrophic. The decision about pregnancy and birth after one or more c sections is something I often discuss with clients (or potential clients). There is very useful information about the industrialised world statistics here https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/assets/downloads/birth-after-previous-caesarean/NPEU_Lay_Summary_planned_mode_of_birth_after_previous_CS_v20_-_231121.pdf

Many years ago I was involved in setting up a number of “youth friendly” sexual health clinics in Sussex. The young people who accessed those had benefited from at least basic biology lessons and personal, health and social education. In combination these raised their awareness of both the need for contraception and the encoded message of “youth friendly” services – that confidential, non judgmental services would be offered to those of all ages. Our belief was that early pregnancy poses major health risks to a woman and so contraceptive provision is a vital part of comprehensive health care. Attending youth discussion groups in Malawi I have discovered that many of the girls don’t even understand the link between sexual intercourse and pregnancy, or the link between menstrual periods and likely fertility.

In practice, very few women in Malawi access contraceptive services before having their first child. It’s hard to imagine that use of the term “family planning” could really resonate with a teenager who doesn’t understand basic biology. It is often referred to here as family spacing, again strengthening the understanding that it is for those who have already had a baby. Women who access maternity services and the child health clinics are offered information about the benefits of family spacing, but, as in the UK, most women who have just had a baby are not really very focussed on thinking about the sex and it’s consequences! Although it is known that the high levels of prolactin created by frequent and exclusive breast feeding can delay the return of fertility for most women, many women will conceive again very quickly. Part of my routine postnatal care is to talk with clients about their contraceptive choices. There is very useful information available from the Breastfeeding Network https://www.breastfeedingnetwork.org.uk/factsheet/contraception/, but a face to face discussion can be extremely helpful, especially for those who have faced fertility challenges or have doubts and questions about what might be best for them . I am happy to provide post birth care even if you haven’t had pregnancy care with me. https://yourmidwife.org.uk/blog/what-midwifery-care-do-you-need-checks-in-pregnancy/.

There are some positive practices which I have seen. At the vaccination clinic yesterday, the staff took the opportunity to share some key messages to the 100+ women waiting patiently. Even better, because it is a community without a local clinic the staff offer administration of contraceptive injections to any who want them. Injectable methods of contraception are a popular choice for many women here, both for ease, but probably more importantly is that they are effectively invisible to their partner. Many men are very much against contraception, apparently believing that the more children they father the higher their social standing. The contraceptive injection is available here as a pre-filled unit for self injection, and it is chemically stable being stored at the high ambient temperatures here. This could be life changing for women who live in the most rural communities for whom travel to a clinic becomes extremely challenging or even impossible during the rainy season. Implants are widely available, with the huge benefit that no further action is needed for 3 or 5 years, depending on the type. Having been taught insertion and removal a great many years ago, I have been fitting and removing these. In the UK we would use a fully sterile kit and sterile gloves. Here, because there are no scalpels to make an incision for the removal, women are told that they must buy a razor blade (they are sold individually wrapped in the market) for us to incise the skin (incidentally women are told to bring a single blade to the hospital when they come to give birth which is used to cut the cord). The forceps used are simply washed (rinsed) and then wiped over with spirit before reuse. I realise that I am starting to accept the incredibly different standards here – but will certainly feel much more comfortable following the strict aseptic technique for procedures that I was taught 40+ years ago as a student nurse!